Leonardo, The Good Place, and St. Francis of Assisi

I had never been to a Catholic funeral before; the running gag over the last few decades was that my aunt and uncle had a Baptist wedding…

I had never been to a Catholic funeral before; the running gag over the last few decades was that my aunt and uncle had a Baptist wedding (short, with no kneeling or communion) and a Catholic reception (booze and dancing, and lots of both).

I had never been to a funeral where the casket was not front and center, or at a funeral home, for that matter. He was tucked into a corner of the cozy midcentury modernist sanctuary; my husband, a frequent and ever-reluctant pallbearer, said it was one of the heaviest caskets he’s ever lifted, even with seven other men to carry it. Part of me thinks that — despite the many pounds my uncle Tom, already a slim man at his peak health, lost during his illness — was no accident.

I’m not sure how many nonbelievers were present for the service, but I do know a large Southern Baptist contingent had made the trek in a looming Cincinnati snow and ice storm, and the avuncular priest made a nod towards the scale and scope of people who had come to honor my uncle. I’m not sure how many of them had also never been to a Catholic funeral, let alone even been inside a Catholic church before; there were strangely ancient papal rites like chanting and incense over his body before he was carried out to the hearse, but there were some truly beautiful traditions I never even knew existed, in any faith or denomination.

Specifically, there were little cards printed with a lovely serene pastel image of St. Francis, cradling a wolf’s paw in one hand as a slightly concerned lamb looks on beside him. I am not Catholic, and I have some series qualms about their leadership and general orthodoxy, but I have a deep appreciation for their worship of the blessed Virgin and the myriad saints and martyrs in their suffering and sacrifices for their faith.

I knew Tom was born and raised Catholic, but I had always known him to be more of a naturalist, a conservationist, a lover of gentle and beautiful things, and I didn’t truly weep that day in the sanctuary until I read the entirety of The Prayer of St. Francis as it was printed on the back of this small, wallet-photo sized (remember carrying photos in your wallet?) card.

We all know it, and have heard it in some way: Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. Us Protestants, however, never really made it past that point, given as we are continually instructed to fear the vengeful God of Abraham whose appetite for smiting sinners was only somewhat abated by the death of his only son. After years in Southern Baptist churches followed by much mellower Methodist attendance, I had hardened myself against this fire and brimstone God, but softened myself towards the few true Christians I knew of in this world: Fred Rogers, Dolly Parton, Bob Ross, Martin Luther King, Jr. But an instrument of “God’s peace” in a world of endless war and suffering, hatred and inhumanity? A dubious role, to me, at best.

Until I read the lines of the second stanza:

O Master, let me not seek as much

To be consoled as to console,

To be understood as to understand,

To be loved as to love…

Because I’d never heard a more perfect embodiment of someone as a person as these lines described my uncle, someone whom I never knew to be particularly devout but was forever kind, gentle, quiet, and supportive. Family Day at the Convent with his beloved nun aunt were as much as I was aware of in terms of his religious affiliation, but then you also don’t really think too much about the family of the man of who marries your mother’s only sister (or at least I didn’t).

His is a large, traditionally Cincinnati West Side German-Irish Catholic brood of six siblings, and I’m disappointed in myself that I never really met or got to know them until his illness grew more dire. We had met in passing every now and then, but never really had the opportunity to have a conversation with any of them. We made small talk in waiting rooms in between his treatments when he was hospitalized in need of a blood transfusion, discussed the local beer scene on my aunt’s couches during extended visits near the end.

His obituary, plain and square in the center of the page in the Enquirer earlier that week summed him up as “Uncle to many;” an understatement. While I always knew that he was my uncle, I never really understood just how many other people were also lucky enough to call him the same, until we were all there in the St. Bartholomew sanctuary, on edge about the impending weather and devastated when they calmly closed the massive casket, handed my aunt his wedding band, and wheeled him forward for the mass.

It was too muddy for a true graveside ceremony, according to the cemetery manager who met us there. My uncle’s plot is in a little valley, surrounded by trees and a bold, barefaced sycamore that I knew he would have loved had he seen it. After days of rain and impending snow/sleet/ice, they didn’t want anyone to slip (no one had signed release forms, I’m sure), and so we listened to more prayers about the Kingdom of Heaven, and sleeping in Jesus, and finding one another in the eternal afterlife. I just wanted to hear more stories about my uncle, things I didn’t know about him but would be wholly unsurprised to learn, as I leaned into my husband and we shivered under a borrowed umbrella.

Believe me: there is nothing I want more than for there to be some place in the sky where we will all end up together, in the prime of our lives, in perfect health, in our idealized state: me, my husband, whatever children we may or may not decide to have depending on the state of the world, my uncle, my grandfather, Prince, my great-grandmother, Carrie Fischer, etc.

Part of me would even settle for TV’s The Good Place, complete with bureaucrat demons in twee bowties and Kierkegaardian thought experiment dilemmas, so long as I could be there with one or two others I loved dearly in this realm. Eternal suffering and/or annoyance can’t be quite so bad as one imagines, except that the few people I’ve known personally and grieved for would have never gone to “The Bad Place” in the first place, leaving me with fellow strangers and nonbelievers and fro-yo fans and people from Jacksonville (seriously, go watch the show, it’s great) to debate existentialism and experience a primetime-friendly version of an eternal cycle of extremely specific torture once a week.

Which makes it even more important to me that the good we do in the world is immediate and tangible, not pre-emptive or overly self-sacrificing. The priests and preachers may claim that those we’ve lost will live on in heaven, but I more strongly believe that they will live on here in the lives of those they touched on earth, those of us still alive, who miss them, who want to be more like them, who want not so much to be understood as to understand.

That line stood out to me apart from all the rest of St. Francis’s prayer: the importance of trying to understand others, of making the effort yourself, instead of grasping to make them understand you. If there’s one thing I ever learned from the quiet, goofy, gentle guy that was my uncle, it was the importance of listening, of waiting until just the right moment to say just right the thing and make everyone’s day a little bit better as a result.

Even as he sat in a hospital bed, awaiting a blood transfusion near the end of his three-year battle with aggressive lung cancer, the same genetic mutation that killed his mother through her ovaries a decade earlier, he made jokes with twinkling eyes and a genuine grin.

For better or for worse, I’m one of those people who likes to think that, for the most part, humans are innately “good.” There’s a lot in the world today that often makes me seriously wonder if I’ve been wrong this whole time, along with all the other self-doubting optimists out there, but there are some people you encounter who not only confirm that belief but your general faith in humanity overall.

Maybe his jokes were only to make the rest of us feel better, which is what I suspect given the amount of pain he was in as the cancer spread to his spine and the fluid surrounding it, affected his vision and impacted his hearing, and it makes me love him and miss his kind of gentle strength even more.

What does etiquette dictate you buy a dying man for Christmas? My uncle was always impossible to shop for to begin with, but as we knew his death grew closer through the holidays, and prayed to whatever we could that he would make it through to January, I struggled to think of something he might want or need, besides a new set of lungs that weren’t eating the rest of him alive from the inside out. In previous, healthy years, I’d gotten him snuggly fleece vests and knit him awkward ribbed caps, a pencil holder made from some kind of a tree trunk that I always conspicuously noticed in his home office every year after.

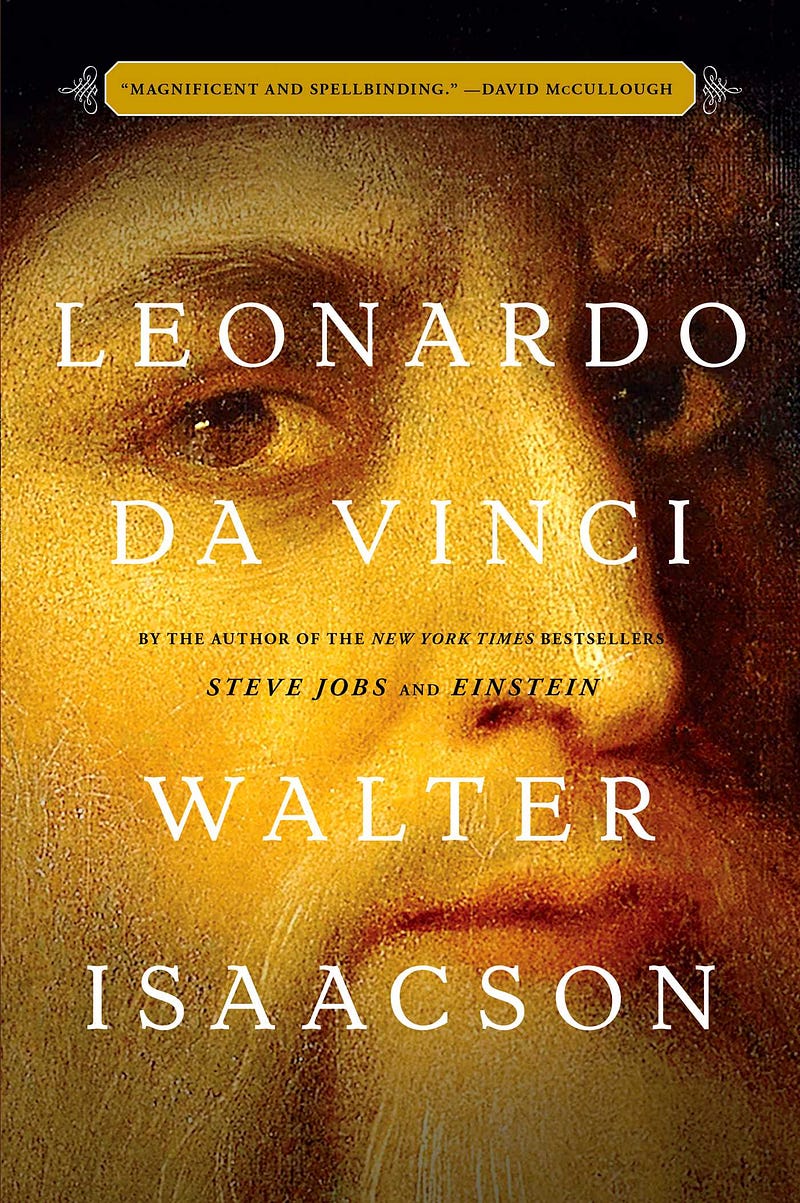

I settled on Walter Isaacson’s hefty new Leonardo da Vinci biography: my uncle was an engineer and scientist as much as he was a naturalist and a woodworker, soccer player and hiker of volcanoes. As he braced himself on the metal arm of the hospice bed and opened his overzealously-wrapped gift (I always use too much tape), he seemed genuinely excited to read it, even though in his frail state he could barely hold the thing up. Maybe he was excited, and maybe he was just that good of a person to make me feel good about the completely impractical gift I’d chosen for him as his life was ending.

By pure coincidence, my mother bought me the same book for the same Christmas as well, and I sent a text to my aunt and uncle with a photo, saying that we should have a book club together in the new year. Only my aunt responded, in enthusiastic emoji. I started reading my copy immediately, and I don’t know if my uncle was ever able to read or open or even lift his to turn the pages and marvel at the illustrations and codices in their careful mirror script.

It is by far the best work of Walter Isaacson’s I’ve read to date (Einstein was my favorite before this one, followed by Steve Jobs and Benjamin Franklin), but every time I pick it up, I wonder about the left-handed vegetarian Renaissance man that was my uncle, and how deeply unfair it was for him to be gone so soon after his 59th birthday, just after his 25th wedding anniversary and receiving a lifetime achievement award from his employer since graduating from college, and donating the prize money back to that college as a scholarship fund for other engineering students.

How cruel it was that he was one of the most healthy, conscientious people I’ve ever known, a championship soccer player, an enthusiastic hiker, only to get aggressive lung cancer, having never smoked in his life.

How heartbreaking and yet perfect it was that even though in his final days he could no longer lift his head or open his eyes because of the havoc the cancer wrought on his nervous system, his heart continued beating strong and true until the rest of his body could no longer support it.

Imagine how a strong a heart that is, to carry the entirety of one’s body for weeks and days at a time.

I can only hope my own is half that strong, after my years of smoking and lack of exercise and red meat and jealousy and pettiness and lack of faith, whenever it is that my time comes. I’ve realized that I am not so much afraid of death, per se, as I am of the manner in which I may die. I don’t know if I have a year of seemingly tireless fight in the face of cancer in me, let alone three, and I marvel that he made it as long as he did.

My own husband half-jokes that cancer will claim him well before either of us are ready, and I had to ask him to stop making that “joke,” no matter how true it may end up being, whether by nature or nurture a vicious random mutation claims one or both of us. He claims that I will live forever, in the tradition of my nonagenarian paternal and octagenarian maternal grandmothers, but after seeing my uncle and before that my grandfather waste away from Parkinson’s, he claims to want to break the cycle of women in my family watching their men fade away slowly as their own bodies break down in the exhausting process of full-time caregiving.

We made it home from luncheon after the funeral just as the ice storm hit, in layers of rain and sleet and dense snowflakes, and I’ve never been one of those who understands the custom of having a catered or potluck meal after burying a loved one. I am one of those who wants to go home immediately and hide from the world after the few funerals I’ve attended; I always exhaust my tiny reserve of small talk and weak smiles early in the day. Since this was a Catholic ceremony, however, beer and wine were available and without judgement, another nuance to the grieving process I hadn’t expected but was also completely unsurprising.

I kept my aunt’s cup of white wine full at her request and allowed myself a beer, ostensibly in honor of my uncle’s long German family line and love of craft beer and homebrewing, but also because we didn’t have beer at home and the stores would be wastelands leftover from panicked bread, eggs, and milk runs. I didn’t want to leave her, there was more I wanted to know after all the years we’d spent not talking about his cancer in an effort to keep things feeling normal for them instead of the disease taking over their lives completely.

I wanted to ask her about his old college friends who sang a futbol drinking chant before toasting in his honor, to know the story behind the gorgeous portrait of her he kept on his nightstand from their younger years where she appears to maybe be topless (but is probably not). I wanted to know the details of the watermelon patch he grew as a child, how and when they decided to get married, tales from his travels to Brazil and Turkey.

I know I will hear these stories sometime in the future, secondhand, but I regret that I did not think to ask him about them sooner.