On Being the Fat Yogi in the Group Picture

I can pinpoint with absolute laser accuracy the moment when, during my second weekend of 200-hr Yoga Teacher Training, I started to fully…

I can pinpoint with absolute laser accuracy the moment when, during my second weekend of 200-hr Yoga Teacher Training, I started to fully question my decision to take on this challenge. Halfway through our first day of the weekend, we’d completed two hour-long classes and a mindfulness workshop, and I was feeling good. Sweaty, stinky, and sure to be sore over the next several days, but good nonetheless.

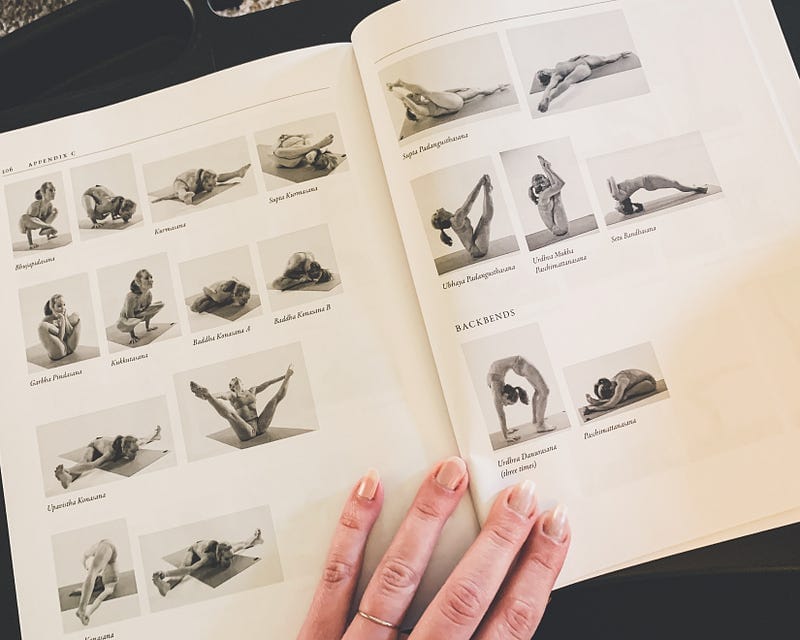

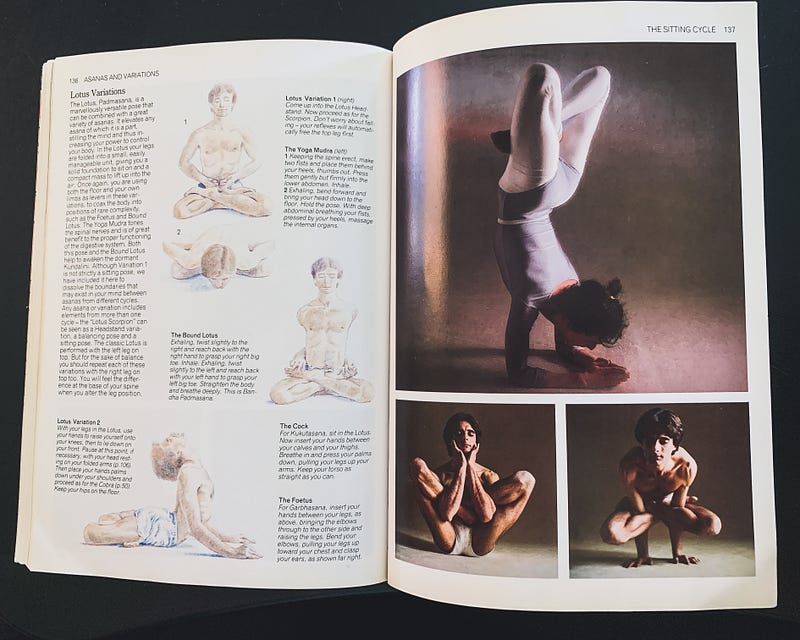

And then we worked on the Primary Series, a prescribed series of Ashtanga Yoga postures ranging from pretty standard like Trikonasana (Triangle), my all-time favorite asana, to the patently absurd like Garba Pindasana (Womb Embryo Pose), where you bind yourself in a lotus position and roll around your mat nine times to represent the nine months of human gestation. For reference, Ashtanga was and is the basis for all of high-impact, fitness-driven “Power Yoga” programs of the 90’s and early Aughts, and while I firmly believe and hope to teach others that yoga is for everyone, the difficult truth is that the Ashtanga Primary Series and its variations and extensions are simply… not.

Somewhere near the end of the standing poses in the series, there came wrapping of arms around the outside of the legs to bind behind the back, pushing hands through lotus-posed legs to lift (and hold) off the floor, and I couldn’t physically do any of it. Forget the lifting, my legs are simply too big to wrap and tuck and twist in the “right” way for many of the poses.

And that’s when the panic hit.

I’ve been practicing yoga asana for nearly 20 years, but also almost entirely on my own and at home. I could never find a studio where I felt like I could belong as a fat yogi. For me, as my weight and mental health fluctuated over the decades, yoga has always been a place of refuge, a space where I could take time to get out of my turbulent head and let myself just exist in my body, no matter what size it happened to be that day. Bringing other people — not to mention mirrors — into the equation ramped up my anxiety, both personal and social, and completely defeated the purpose.

But earlier this year, when vaccines were unclear and WFH life still had no real end in sight, I finally did what I’d wanted to do for years and signed up for a YTT-200 course at a local studio I’d never even been to before, let alone practiced in. It had been more than three years since I’d practiced at a studio, but as much as I dislike practicing with others, I still wanted to deepen my own practice and share yoga in all its many facets with others. I especially want to help folks who may believe that yoga is only for the thin white straight cisgender women in seamless white outfits on Instagram, contorting themselves impossibly on white sand beaches with faces devoid of all but bland blissfulness, to see that yes, yoga is for them, too.

I signed up, got my books, met with the studio owner and trainer (a yogi PhD with expertise in Ayurveda, another holistic Indian practice I want to learn), and the first weekend I attended was great. Exhausting and humbling, but great: I learned I have overextended my joints for most of my life, relying too much on my natural flexibility instead of building strength in many of the asanas I thought I had mastered. I dug into the 8 Limbs of Yoga, of which asana is only one part of a fully integrated philosophy & practice, and started exploring pranayama, or controlled breathing, as well as meditation, which I thought I would never be able to do given my constantly-busy, adult-diagnosed inattentive ADHD brain. It’s still a challenge, but in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, this is actually the true goal of yoga:

1.2 — Yogas citta vrtti nirodhah: yoga is the cessation of the modifications, or fluctuations, of the mind.

AKA what yoga had already been helping me with for the better part of two decades.

After that first weekend I found myself loving my practice even more and digging even deeper into all the essential layers and levels of yoga. I finally started enjoying group classes, because I felt more connected to the teachers and the other regular students.

It also doesn’t hurt that there are no mirrors in this studio.

I cannot begin to describe how much of a difference this deceptively unimportant feature makes in my ability to focus on my practice on my own mat instead of staring at my rolls reflected back at me or trying not to stare at a slim, bendy person up front seemingly only made of skin and muscle, not a bone or an ounce of fat to be found on their perfectly-aligned form.

But by my second weekend, we started really leaning in on the Ashtanga Primary Series, and I came home after our first 12-hour training day exhausted, frustrated, and embarrassed at myself, my unruly body, my expansive thighs and thick calves, my lack of discipline, my poor upper body strength, my inconsistency and my inability to truly dedicate myself to practice in terms of doing it every single day without question or complaint.

What was I doing and who did I think I was?

Who wants to learn about yoga from a fat late-mid-Thirtysomething Millenniold who can’t even do a headstand and has been doing Downward fucking Dog incorrectly for the last 15 years?

Why did I ever think I’d be good at any of it when I abandon projects and hobbies all the time, much to my own shame and often financial detriment?

(Hello, Herbal Cosmetic Formulation courses I bought last spring at peak quarantine! Hello, novel I’ve been “working on” for three years now and only have three chapters done, and you too, memoir I wanted to start this spring! Hello, yarn stash that’s lain dormant, tarot cards left dusty, kettlebells I can no longer swing!)

After a lengthy, much needed ugly-cry on my spouse’s shoulder, I went to bed early and woke up sore all over from 3+ hours of practice, but not ready to throw in the towel just yet.

On Sunday, we stood in a class of long-time local yogis, who all know each other but hadn’t practiced together since before the pandemic. Our Instructor-emeritus and Philosophy teacher led us in a complete 90-minute Primary Series, and in the midst of all the deep ujayii breathing and extensive sweating and adjusting my alignment on poses I could do and finding modifications for those I couldn’t, I realized that not only did I not care whether I could achieve the advanced poses, but no one else did either. And I wasn’t the only one who couldn’t do all of them either, whether due to body type/size or physical limitations. The poses were not the point — and they shouldn’t be.

I set a goal for myself at the start of 2021 that I would work to achieve several asanas unavailable to me in the past: crow pose, wheel (which I used to be able to do 15 years/30 pounds ago) and the absolutely dreaded headstand. I attempted a headstand in that Primary Series and nearly had a full-on panic attack at balancing my big ol’ body on my little-ass head. The Instructor came to assist but sensed my apprehension, encouraging me simply to work on getting used to being inverted. I tried not to sob as I collapsed in a heap from a tripod dolphin position and reached back into child’s pose, closing my eyes to catch the tears and focusing on my shaking breath to calm myself as much as I could:

In.

Out.

In.

Out.

Final relaxation in Shivasana never felt so cathartic.

Afterwards, there were sweaty hugs and tired high-fives all around; someone called for a group picture, and my relief at just getting through the previous 90 minutes swelled into a feet more visceral than my asana anxiety: the fear of being photographed. And not just photographed in general, but being photographed while sweaty, red-faced and makeup-free, wearing a more body-revealing outfit than I would ever wear in public — just a crop top and high-waisted leggings set, having shed my tank top mid-practice after soaking it through with sweat.

My heart sank even further when I saw the picture afterwards, me conspicuously standing awkwardly apart from the rest of the group and conspicuously larger than the other yogis, despite my best efforts to angle myself differently.

I’m still not particularly happy with this photo, but I’m working on being okay with it. If anything, I’m happy about just making it through that Primary Series without injuring myself or completely giving up. I’m loving what I’ve learned so far about yoga and everything it entails beyond a narrow perfectionist Western focus on fitness and aesthetics. And I’m excited for the opportunity to keep working on those anxiety-inducing asanas, to keep learning about my own body and its potential for growth and change.

I’m also finally starting to be okay with the possibility that I may never be able to achieve some of those advanced asanas that simply will not work for my body. I don’t plan to teach a strict Ashtanga or Primary Series practice, but they’re important to learn and respect as part of the complete yoga tradition and philosophy.

I don’t know if anyone will want to take a class from a fat yogi, but I hope someone does and I hope I can help them find their own sense of space and strength in physical practice as well as that elusive sensation of calm that felt impossible until they arrived on their mat and closed their eyes to breathe.

The one thing I do know for sure in this process is that it’s all practice. That’s why we call yoga a practice, not a routine or a regimen; the desired outcome shouldn’t necessarily be “perfection” as defined by a centuries-old text or by a “guru” with a popular internet presence who doesn’t know an individual’s physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual goals.

The ultimate goal is just as Patanjali noted in Sutra 1.2: the calming of the mindstuff, no matter how advanced or how new you are. And that might be both the most challenging — and ultimately rewarding — yoga practice any of us can work towards.